Note: This text has been automatically extracted via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software.

Performance Of The Agamemnon Of Aeschylus At Balliol College, Oxford.

sky under which the Agamemnon was first performed , ancl tho gaslight which illumined the presentation of last * Thursday . Shorn of its inspiring local and religions associations , a Greek tragedy cannot but bo an anachronism . The theatre at Athens ( in the time of yBsch yhis at any rate ) Avas a sacred place , and tbe drama an act of public worship . In tbe most prominent position , in the centre of tbe " orchestra" or dancing-placeon AA'hich the Chorus stood

, , , ivas the " tbymele , " or altar of Dionysus , the central point of tbe choral dances ; the place of honour in the chief seats immediately round the orchestra Avas occupied by- the priest of Dionysus , Avith the priest of Apollo on his right and tbe priest of Zeus " Pollens" on bis left ; and , above all , the story to be represented was felt b y the AA-bole audience to be sacred , inasmuch as its personages were the gods and heroes of their race—tbe familiar names of that

mythical antiquity which had such realit y for a Greek , and into which all tbe existing threads of family ancl social and national life ran back . "A Greek tragedy , " says Professor Jebb , in bis admirable little " Primer of Greek Literature "—

Could bring before a vast Greek audience , in a grandly simple form , harmonised by choral music and dance , the groat figures of their religious and civil history . The picture had at once ideal beauty of tho highest kind , and for Greeks a deep reality -, they seemed to be looking at tho actual beginning of those rites and usages which were most dear and sacred iu their daily life .

In a modern presentment all this is , of course , lost ; nor can it be compensated for by external features of the drama , by skill in acting , for example , or play of feature , or variety of costume ancl scenery . Greek plays were not written with a view to such "theatrical" considerations . . There was but little animated gesture or movement on tbe stage . Tbe two or three actors stood more like a group of majestic statues , wearing appropriate masks ( play of feature

would bave been lost on tbe spectators in the vast open-air theatre ) , and made up to look larger than human Avitb a sort of hi gh Avig and very thick-soled boots or buskins ( the gntudes cothurni especiall y identified with tragedy ) . Their costume was never merel y theatrical , suited to different parts ; but Avas of one general type—viz ., that Avorn at processions of the god Dionysus , a long striped robe , with a broad band or girdle , ancl over this a mantle of ' bright colour .

The " scene" at the back of the stage ( a high wall covered with hangings or painted w * oochvork representing a temple or palace ) was hardl y ever changed—the Ajax of Sophocles ancl Eumenidcs of iEschylus being , perhaps , the only extant tragedies in which this could have been done—but partial changes of side scenery were effected by means of triangular prisms revolving upon pivots at the side of the stage : and there ivere certain mechanical appliances for sboiving tbe interior of a house through the open doorand for

, suspending gods in the air . There was much less room for acting or theatrical effect than on the modem stage ; ancl tbe effect depended far more on the religions and patriotic sympathies and active intellectual interest of tbe ori ginal audience . Without that audience and its peculiar feelings and associations any real " reproduction" of a Greek drama is impossible . It is an interesting experimentbut an obvious anachronism .

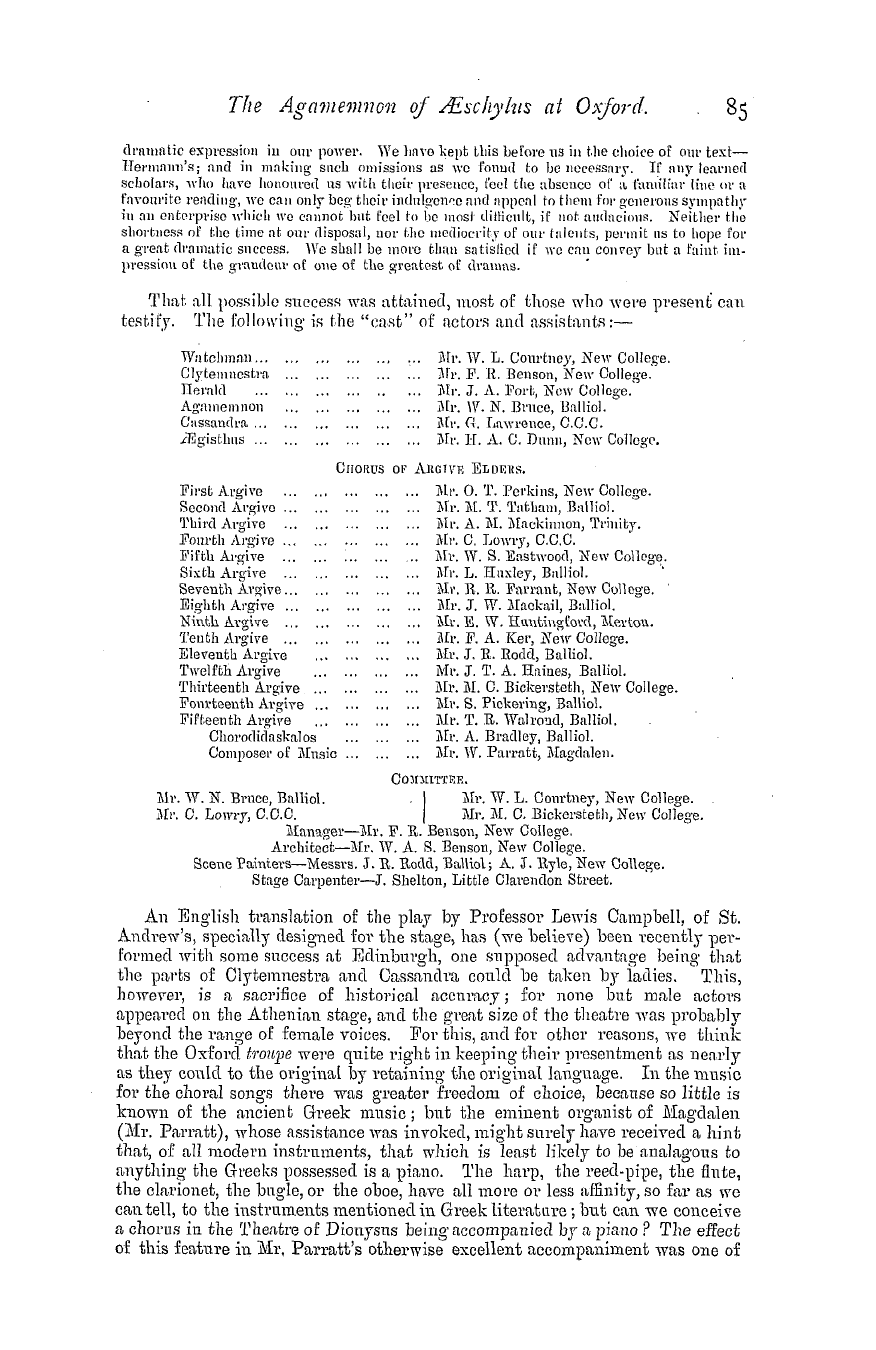

, We have premised these remarks , not in disparagement of tbe attempt to represent the Agamemnon , but to show the reall y insuperable difficulties under which it was made , and the impossibility of judging it by the standard of modem criticism . That the actors themselves ivere aware of this appears from a short notice prefixed to their " plav-bill , " in which tbey

are—Anxious to disclaim any intention of producing- a facsimile of a Greek drama . Were such a thing possible , to all but antiquarians it Avould seem grotesque and unmeaning ' . AVe have , therefore , been guided throughout by tho one desire of giving to this work the best

Note: This text has been automatically extracted via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software.

Performance Of The Agamemnon Of Aeschylus At Balliol College, Oxford.

sky under which the Agamemnon was first performed , ancl tho gaslight which illumined the presentation of last * Thursday . Shorn of its inspiring local and religions associations , a Greek tragedy cannot but bo an anachronism . The theatre at Athens ( in the time of yBsch yhis at any rate ) Avas a sacred place , and tbe drama an act of public worship . In tbe most prominent position , in the centre of tbe " orchestra" or dancing-placeon AA'hich the Chorus stood

, , , ivas the " tbymele , " or altar of Dionysus , the central point of tbe choral dances ; the place of honour in the chief seats immediately round the orchestra Avas occupied by- the priest of Dionysus , Avith the priest of Apollo on his right and tbe priest of Zeus " Pollens" on bis left ; and , above all , the story to be represented was felt b y the AA-bole audience to be sacred , inasmuch as its personages were the gods and heroes of their race—tbe familiar names of that

mythical antiquity which had such realit y for a Greek , and into which all tbe existing threads of family ancl social and national life ran back . "A Greek tragedy , " says Professor Jebb , in bis admirable little " Primer of Greek Literature "—

Could bring before a vast Greek audience , in a grandly simple form , harmonised by choral music and dance , the groat figures of their religious and civil history . The picture had at once ideal beauty of tho highest kind , and for Greeks a deep reality -, they seemed to be looking at tho actual beginning of those rites and usages which were most dear and sacred iu their daily life .

In a modern presentment all this is , of course , lost ; nor can it be compensated for by external features of the drama , by skill in acting , for example , or play of feature , or variety of costume ancl scenery . Greek plays were not written with a view to such "theatrical" considerations . . There was but little animated gesture or movement on tbe stage . Tbe two or three actors stood more like a group of majestic statues , wearing appropriate masks ( play of feature

would bave been lost on tbe spectators in the vast open-air theatre ) , and made up to look larger than human Avitb a sort of hi gh Avig and very thick-soled boots or buskins ( the gntudes cothurni especiall y identified with tragedy ) . Their costume was never merel y theatrical , suited to different parts ; but Avas of one general type—viz ., that Avorn at processions of the god Dionysus , a long striped robe , with a broad band or girdle , ancl over this a mantle of ' bright colour .

The " scene" at the back of the stage ( a high wall covered with hangings or painted w * oochvork representing a temple or palace ) was hardl y ever changed—the Ajax of Sophocles ancl Eumenidcs of iEschylus being , perhaps , the only extant tragedies in which this could have been done—but partial changes of side scenery were effected by means of triangular prisms revolving upon pivots at the side of the stage : and there ivere certain mechanical appliances for sboiving tbe interior of a house through the open doorand for

, suspending gods in the air . There was much less room for acting or theatrical effect than on the modem stage ; ancl tbe effect depended far more on the religions and patriotic sympathies and active intellectual interest of tbe ori ginal audience . Without that audience and its peculiar feelings and associations any real " reproduction" of a Greek drama is impossible . It is an interesting experimentbut an obvious anachronism .

, We have premised these remarks , not in disparagement of tbe attempt to represent the Agamemnon , but to show the reall y insuperable difficulties under which it was made , and the impossibility of judging it by the standard of modem criticism . That the actors themselves ivere aware of this appears from a short notice prefixed to their " plav-bill , " in which tbey

are—Anxious to disclaim any intention of producing- a facsimile of a Greek drama . Were such a thing possible , to all but antiquarians it Avould seem grotesque and unmeaning ' . AVe have , therefore , been guided throughout by tho one desire of giving to this work the best