-

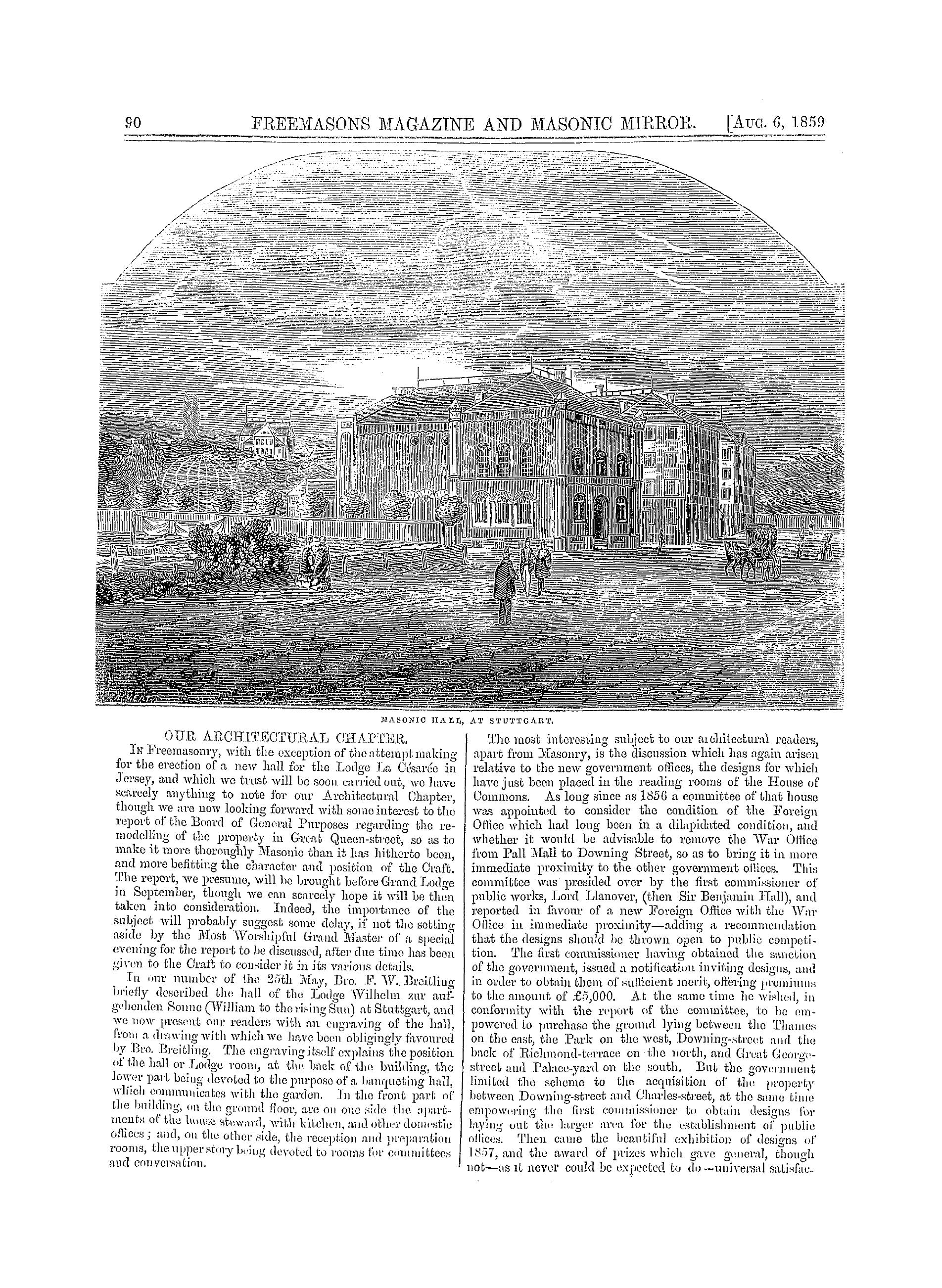

Articles/Ads

Article THE FAMILY OF THE GUNS. ← Page 3 of 3 Article THE WORK OF IRON, IN NATUREART, AND POLICY. Page 1 of 4 →

Note: This text has been automatically extracted via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software.

The Family Of The Guns.

less . It scatters a thousand bolts of fire about at any desired point . It Avill root up a tree , knock down a great house , or sink the largest ship at three miles . This -will it do Avith unfailing accuracy , and Avill repeat the deed many times Avithin a given period . Surel y it is therefore a providential laAV which evolves peace and good will , even out of the fears of men , and p laces upon the shoulders of the ambitious the responsibilit y of entering upon Avar .

The Work Of Iron, In Natureart, And Policy.

THE WORK OF IRON , IN NATUREART , AND POLICY .

F 1 J 01 I " THE TWO PATHS , " JiY JOIIX I . USKIKT , M . A . AVHEX I venture to speak about my own special business of art , it is almost always before students of art , among whom I may sometimes permit myself to he chill , if lean fed that lam useful : but a mere talk about art , especially ivithout examples to refer to ( and I have been unable to prepare any careful illustrations for this lecture ) , is seldom of much interest to a general audience .

As 1 was considering what you might best hear with mc in speaking about , there came naturally into my mind a subject connected with the ori gin and present prosperity of the town you live in : and , it seemed to me , in the out-branchings of it , capable of a very general interest . When , long ago ( I am afraid to think how long ) , Tunbriclge AVells Avas my Switzerland , ancl I used to be brought down here in the summer , a sufficiently active child , rejoicing in the '

hope of clambering sandstone cliffsof stupendous hei ght above the common , there used sometimes , as , I suppose , there arc in the lives of all children at the AVells , to be dark clays in my life—clays of condemnation to the pantiles ancl band—under Avhich calamities my only consolation used to be in watching , at every turn in my walk , the welling forth of the spring over the orange rim of its marble basin . The memory of the clear watersparkling its

, over sail roil stain , came back to mc as the strongest image connected Avith the place ; and it struck mc that you mi ght not be unwilling to-ni ght , to think a little over the full significance of that saffron stain , and ofthe power , in other ways and other functions , of the steely clement to which so many here owe returning strength and life;— chief as it lias been always , and is yet more and more markedl y so day by day , among the precious gifts ofthe earth . The subject isof

, course , too wide to be more than suggestively treated ; and even my suggestions must be few , and drawn chiefly from my own fields of work ; ncA-erthclcss , I think I shall have time to indicate sonic courses of thought Avhich you may afterwards follow out for yourselves if they interest you ; and so I will not shrink from the full scope of the subject which I have announced to you—the functions of Iron , in Nature , Art , and Policy . AVithout more preface I will take up the first head .

i . / rim m ivature . —1 ' ou will probably know that the ochrcous stain , which , perhaps , is often thought to spoil the basin of your spring , is iron m a state of rust ; and when you sec rusty iron in other places , you generally think not only that it spoils the places it stains , but that it is spoiled itself—that rusty iron is spoiled iron I or most of our uses it generall y is so ; and because AVC cannot use a rusty knile or razor so well as a polished one , wc suppose it to be defect in iron that it is

a great subject to rust . But not at all On the contrary , the most perfect and useful state of it is that ochrcous stain ; and therefore it is endowed with so ready a disposition to get itself into that state . It is not a fault in the iron but a virtue , to be so fond of getting rusted , for in that condition it fulfils its most important functions in the universe , ancl most kindl y duties to mankind . Nay , in a certain sense , and almost a literal

one , wc may say that iron rusted is living ; but when pure or polished , dead . You all jirobabl y know that in the mixed air ive breathe , the part of it essentiall y needful to ns is called oxyeu ; and that this substance is to all animals , in the most acute sense of the word , " breath of life . " The nervous power of life is a different thing ; but . the supporting clement of the breath , Avithout which the bloodand therefore the lifecannot be nourishedis

, , , this oxygen . Now it is this very same air which the iron breathes Avhen it gets rusty . It takes the oxygen from the atmosphere as eagerly as wc do , though it uses it differently . The iron keeps all that it gets ; Ave , and other animals , part ' with it again ; but the metal absolutel y keeps what it has once received of this aerial gut ; and the ochrcous dust ivhich we so much despise is , in fiict , just so much nobler than ironin far it is iron and the

pure , so as air . Nobler , and more useful—for , indeed , as I shall he able to show you presentl y , the main service of this metal , and of all other metals , tons , is not iu making knives , ancl scissors , and pokers , and pans , but in making the ground wc feed from , and nearly all tiie substances first ncctllul to our existence . For these are all

nothing but metals ancl oxygen—metals with breath put into them . Sand , lime , clay , and the rest ofthe earths—potash ancl soda , and the rest of the alkalies—arc all of them metals which have undergone this , so to speak , vital change , ancl have been rendered lit for the service of man hy permanent unity with the purest air ivhich he himself breathes . There is only one metal which docs not rust readily ; and that , in its influence on man hitherto , has caused

death rather than life ; it will not be put to its right use till it is made a pavement of , and so trodden under foot . Is there not something striking in this fact , considered largely as one oftlic types , or lessons , furnished by the inanimate creation ? Here you have your hard , bright , cold , lifeless metal—good enough for swords and scissors—but not for food . You think , perhaps , that your iron is wonderfully useful in a pure formbut how ivould

, you like the Avorld , if all your meadoAvs , instead of grass , grew nothing but iron ivirc—if all your arable ground , instead of beingmade of sand and clay , were suddenly turned into flat surfaces of steel—if the whole earth , instead of its green and glowing sphere , rich with forest and flower , showed nothing but the image of the vast furnace of a ghastly engine—a globe of black , lifeless , excoriated metal ? It ivould he that—probabl y it was once that ; but

assuredly it ivould be , were it not that all . the substance of which it is made sucks and breathes the brilliancy of the atmosphere ; ancl , as it breathes , softening from its merciless hardness , it falls into fruitful and beneficent dust ; gathering itself again into the earths from ivhich AVC feed ; and the stones with which ive build ; —into the rocks that frame the mountains , and the sands that bind the sea . Hence , it is impossible for yoa to take up the most

insignificant pebble at your feet , ivithout being able to read , if you like , this curious lesson in it . You look upon it at first as if it ivere earth only . Way , it answers , "I am not earth—I am earth and air in one ; part of that blue heaven which you love , and long For , is already in me ; it is all my life—ivithout it . 1 should be nothing , and able for nothing ; I could not minister to you , nor nourish you—I should be a cruel and helpless thing ; but , because there is , according to my need aud place iu creation , a kind of soul in mc , I have become capable of good , and helpful in the circles of i-italitv . "

In these days of swift locomotion I may doubtless assume that most of my audience have been somewhere out of England—have been in Scotland , or France , or Switzerland . Whatever may have been their impression , ou returning to their own country , of its superiority or inferiority in other respects , they cannot but have felt one thing about it—the comfortable look of its towns and villages . Foreign towns arc often very picturesque , very

beautiful , but they never have quite that look of warm self-sufficiency and wholesome quiet with ivhich our villages nestle themselves down among the green fields . Ifyou will take the trouble to examine into the sources of this impression , you will find that by far the greater part of that warm and satisfactory appearance depends upon the rich scarlet colour of the bricks and tiles . It docs not belong to the neat building—a very neat building has an

uncomfortable rather than a comfortable look—but it depends upon the warm building ; our villages arc dressed in red tiles as our old Avomen arc in red cloaks ; ancl it docs not matter how worn the cloaks , or how bent and bowed the roof may be , so long as there arc no holes iu either one or the other , and the sobered but imcxtinguishable colour still glows in the shadow of the hood , ancl burns among the green mosses of the gable . And what do you

suppose dyes your tiles of cottage roof ? You don't paint them . It is nature AVIIO puts all that lovely vermilion into the clay for ) 'ou ; and all that lovcty vermilion is this oxide of iron . Think , therefore , Avl ~" ii your streets of tonus would become—ugly enough , indeed , already , some of them , but still comfortable looking—if instead of that warm brick red , the houses became all pepper-andsalt colour . Fancy your country villages chaiigiiigfrom that homel

y scarlet of theirs ivhich , in its sweet suggestion of laborious peace , is as honourable as the soldiers' scarlet of' laborious battle—suppose all those cottage roofs , I say , turned at once into the colour of unbaked clay , the colour of street gutters in rainy weather . That ' s what they would be , ivithout iron .

There is , however , yet another effect of colour in our English country towns ivhich , perhaps , you may not all yourselves have noticed , but for which you must take the word of a sketcher . They arc not so often merely warm scarlet as they are warm purpic ;—a more beautiful colour still : and they owe this colour to a mingling ivith the vermilion of the deep greyish or purple hue of our line Welsh slates emthe more respectable roofs , made more

blue still by the colour of intervening atmosphere . Ifyou examine one of these AVelsh slates freshly broken , you will find its purple colour clear ancl vivid ; and although never strikingly so after it has been long exposed to weather , it always retains enough of the

Note: This text has been automatically extracted via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software.

The Family Of The Guns.

less . It scatters a thousand bolts of fire about at any desired point . It Avill root up a tree , knock down a great house , or sink the largest ship at three miles . This -will it do Avith unfailing accuracy , and Avill repeat the deed many times Avithin a given period . Surel y it is therefore a providential laAV which evolves peace and good will , even out of the fears of men , and p laces upon the shoulders of the ambitious the responsibilit y of entering upon Avar .

The Work Of Iron, In Natureart, And Policy.

THE WORK OF IRON , IN NATUREART , AND POLICY .

F 1 J 01 I " THE TWO PATHS , " JiY JOIIX I . USKIKT , M . A . AVHEX I venture to speak about my own special business of art , it is almost always before students of art , among whom I may sometimes permit myself to he chill , if lean fed that lam useful : but a mere talk about art , especially ivithout examples to refer to ( and I have been unable to prepare any careful illustrations for this lecture ) , is seldom of much interest to a general audience .

As 1 was considering what you might best hear with mc in speaking about , there came naturally into my mind a subject connected with the ori gin and present prosperity of the town you live in : and , it seemed to me , in the out-branchings of it , capable of a very general interest . When , long ago ( I am afraid to think how long ) , Tunbriclge AVells Avas my Switzerland , ancl I used to be brought down here in the summer , a sufficiently active child , rejoicing in the '

hope of clambering sandstone cliffsof stupendous hei ght above the common , there used sometimes , as , I suppose , there arc in the lives of all children at the AVells , to be dark clays in my life—clays of condemnation to the pantiles ancl band—under Avhich calamities my only consolation used to be in watching , at every turn in my walk , the welling forth of the spring over the orange rim of its marble basin . The memory of the clear watersparkling its

, over sail roil stain , came back to mc as the strongest image connected Avith the place ; and it struck mc that you mi ght not be unwilling to-ni ght , to think a little over the full significance of that saffron stain , and ofthe power , in other ways and other functions , of the steely clement to which so many here owe returning strength and life;— chief as it lias been always , and is yet more and more markedl y so day by day , among the precious gifts ofthe earth . The subject isof

, course , too wide to be more than suggestively treated ; and even my suggestions must be few , and drawn chiefly from my own fields of work ; ncA-erthclcss , I think I shall have time to indicate sonic courses of thought Avhich you may afterwards follow out for yourselves if they interest you ; and so I will not shrink from the full scope of the subject which I have announced to you—the functions of Iron , in Nature , Art , and Policy . AVithout more preface I will take up the first head .

i . / rim m ivature . —1 ' ou will probably know that the ochrcous stain , which , perhaps , is often thought to spoil the basin of your spring , is iron m a state of rust ; and when you sec rusty iron in other places , you generally think not only that it spoils the places it stains , but that it is spoiled itself—that rusty iron is spoiled iron I or most of our uses it generall y is so ; and because AVC cannot use a rusty knile or razor so well as a polished one , wc suppose it to be defect in iron that it is

a great subject to rust . But not at all On the contrary , the most perfect and useful state of it is that ochrcous stain ; and therefore it is endowed with so ready a disposition to get itself into that state . It is not a fault in the iron but a virtue , to be so fond of getting rusted , for in that condition it fulfils its most important functions in the universe , ancl most kindl y duties to mankind . Nay , in a certain sense , and almost a literal

one , wc may say that iron rusted is living ; but when pure or polished , dead . You all jirobabl y know that in the mixed air ive breathe , the part of it essentiall y needful to ns is called oxyeu ; and that this substance is to all animals , in the most acute sense of the word , " breath of life . " The nervous power of life is a different thing ; but . the supporting clement of the breath , Avithout which the bloodand therefore the lifecannot be nourishedis

, , , this oxygen . Now it is this very same air which the iron breathes Avhen it gets rusty . It takes the oxygen from the atmosphere as eagerly as wc do , though it uses it differently . The iron keeps all that it gets ; Ave , and other animals , part ' with it again ; but the metal absolutel y keeps what it has once received of this aerial gut ; and the ochrcous dust ivhich we so much despise is , in fiict , just so much nobler than ironin far it is iron and the

pure , so as air . Nobler , and more useful—for , indeed , as I shall he able to show you presentl y , the main service of this metal , and of all other metals , tons , is not iu making knives , ancl scissors , and pokers , and pans , but in making the ground wc feed from , and nearly all tiie substances first ncctllul to our existence . For these are all

nothing but metals ancl oxygen—metals with breath put into them . Sand , lime , clay , and the rest ofthe earths—potash ancl soda , and the rest of the alkalies—arc all of them metals which have undergone this , so to speak , vital change , ancl have been rendered lit for the service of man hy permanent unity with the purest air ivhich he himself breathes . There is only one metal which docs not rust readily ; and that , in its influence on man hitherto , has caused

death rather than life ; it will not be put to its right use till it is made a pavement of , and so trodden under foot . Is there not something striking in this fact , considered largely as one oftlic types , or lessons , furnished by the inanimate creation ? Here you have your hard , bright , cold , lifeless metal—good enough for swords and scissors—but not for food . You think , perhaps , that your iron is wonderfully useful in a pure formbut how ivould

, you like the Avorld , if all your meadoAvs , instead of grass , grew nothing but iron ivirc—if all your arable ground , instead of beingmade of sand and clay , were suddenly turned into flat surfaces of steel—if the whole earth , instead of its green and glowing sphere , rich with forest and flower , showed nothing but the image of the vast furnace of a ghastly engine—a globe of black , lifeless , excoriated metal ? It ivould he that—probabl y it was once that ; but

assuredly it ivould be , were it not that all . the substance of which it is made sucks and breathes the brilliancy of the atmosphere ; ancl , as it breathes , softening from its merciless hardness , it falls into fruitful and beneficent dust ; gathering itself again into the earths from ivhich AVC feed ; and the stones with which ive build ; —into the rocks that frame the mountains , and the sands that bind the sea . Hence , it is impossible for yoa to take up the most

insignificant pebble at your feet , ivithout being able to read , if you like , this curious lesson in it . You look upon it at first as if it ivere earth only . Way , it answers , "I am not earth—I am earth and air in one ; part of that blue heaven which you love , and long For , is already in me ; it is all my life—ivithout it . 1 should be nothing , and able for nothing ; I could not minister to you , nor nourish you—I should be a cruel and helpless thing ; but , because there is , according to my need aud place iu creation , a kind of soul in mc , I have become capable of good , and helpful in the circles of i-italitv . "

In these days of swift locomotion I may doubtless assume that most of my audience have been somewhere out of England—have been in Scotland , or France , or Switzerland . Whatever may have been their impression , ou returning to their own country , of its superiority or inferiority in other respects , they cannot but have felt one thing about it—the comfortable look of its towns and villages . Foreign towns arc often very picturesque , very

beautiful , but they never have quite that look of warm self-sufficiency and wholesome quiet with ivhich our villages nestle themselves down among the green fields . Ifyou will take the trouble to examine into the sources of this impression , you will find that by far the greater part of that warm and satisfactory appearance depends upon the rich scarlet colour of the bricks and tiles . It docs not belong to the neat building—a very neat building has an

uncomfortable rather than a comfortable look—but it depends upon the warm building ; our villages arc dressed in red tiles as our old Avomen arc in red cloaks ; ancl it docs not matter how worn the cloaks , or how bent and bowed the roof may be , so long as there arc no holes iu either one or the other , and the sobered but imcxtinguishable colour still glows in the shadow of the hood , ancl burns among the green mosses of the gable . And what do you

suppose dyes your tiles of cottage roof ? You don't paint them . It is nature AVIIO puts all that lovely vermilion into the clay for ) 'ou ; and all that lovcty vermilion is this oxide of iron . Think , therefore , Avl ~" ii your streets of tonus would become—ugly enough , indeed , already , some of them , but still comfortable looking—if instead of that warm brick red , the houses became all pepper-andsalt colour . Fancy your country villages chaiigiiigfrom that homel

y scarlet of theirs ivhich , in its sweet suggestion of laborious peace , is as honourable as the soldiers' scarlet of' laborious battle—suppose all those cottage roofs , I say , turned at once into the colour of unbaked clay , the colour of street gutters in rainy weather . That ' s what they would be , ivithout iron .

There is , however , yet another effect of colour in our English country towns ivhich , perhaps , you may not all yourselves have noticed , but for which you must take the word of a sketcher . They arc not so often merely warm scarlet as they are warm purpic ;—a more beautiful colour still : and they owe this colour to a mingling ivith the vermilion of the deep greyish or purple hue of our line Welsh slates emthe more respectable roofs , made more

blue still by the colour of intervening atmosphere . Ifyou examine one of these AVelsh slates freshly broken , you will find its purple colour clear ancl vivid ; and although never strikingly so after it has been long exposed to weather , it always retains enough of the